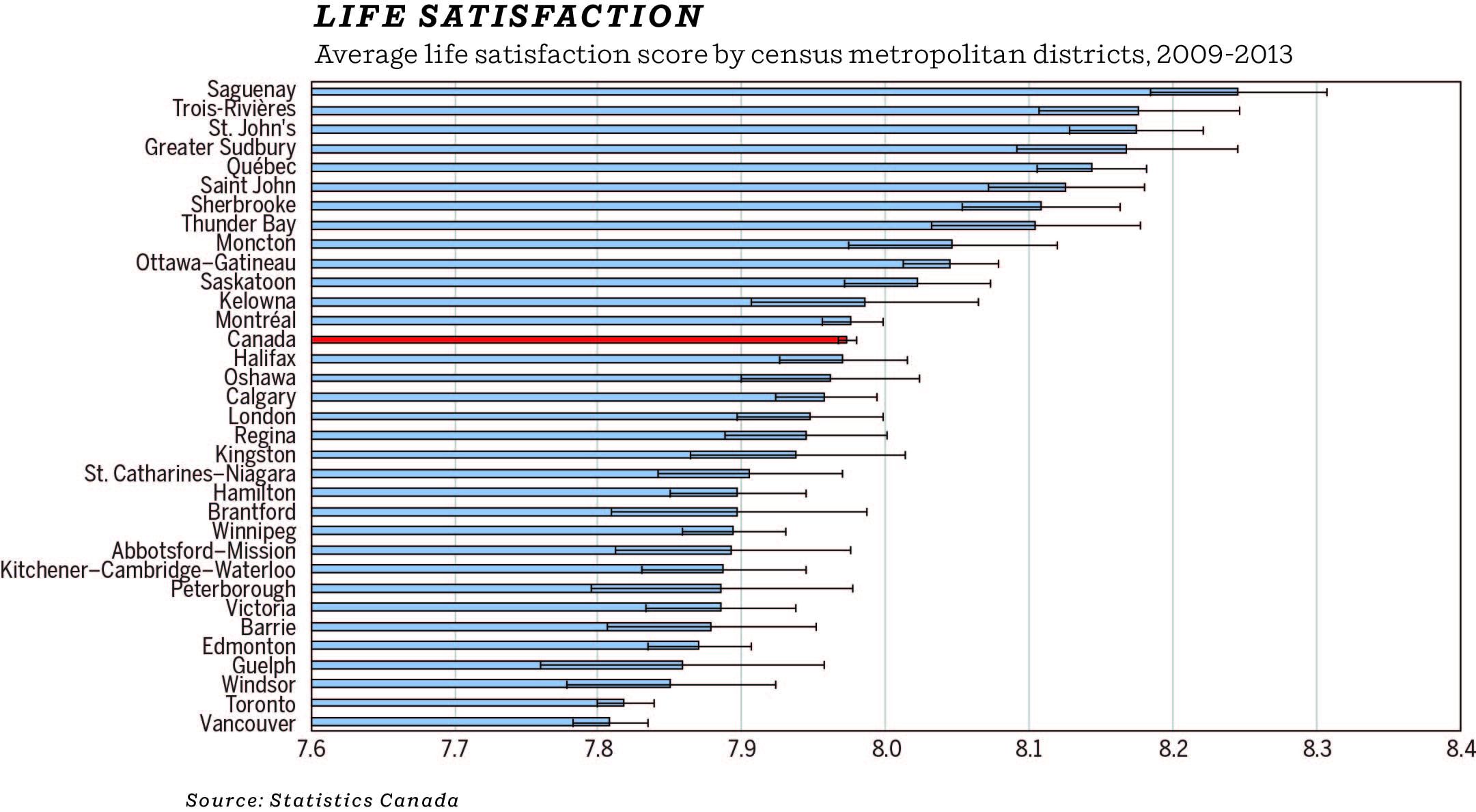

Metro Vancouver and Toronto are Canada’s most unhappy cities. It’s worth figuring out why.

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="180"]

Vancouver and Toronto feature the four factors most correlated with Canadian unhappiness, according to a groundbreaking study out of UBC’s Vancouver School of Economics and McGill University.

Metro Vancouver and Toronto are known for the qualities that characterize the country’s least happy regions: Long traffic commutes, stratospheric housing prices, high population densities and large proportions of foreign-born residents.

Even though scholars have not proved these factors are the direct causes of Vancouver and Toronto residents exhibiting the least life satisfaction of 98 communities in Canada, the researchers found they are strongly correlated to residents’ lack of a sense of well-being and belonging.

In a new study titled How Happy are Your Neighbours?

, John Helliwell, Hugh Shiplett and Christopher Barrington-Leigh discovered Canadians are happier in smaller towns. “We found life to indeed be less happy in the cities,” they write. “This was despite higher incomes, lower unemployment rates and higher education in the urban areas.”

But why did Metro Vancouver and Toronto in particular score so miserably? The United Nation’s 2018 World Happiness Report, which Helliwell co-authored, ranked Canada the seventh happiest country. But recent research by Helliwell and his colleagues reveals sharp differences between the country’s rural towns and high-density city neighbourhoods.

A closer look at the findings for Metro Vancouver reveals residents of South Surrey, Langley, West Vancouver and parts of North Vancouver are among the happiest. The least content are in east Vancouver, North Surrey, south Burnaby and Richmond. Figuring out why exactly is complex.

It’s intuitive that long commutes and housing unaffordability make people anxious or depressed, but the study’s more unexpected unhappiness links were with density and foreign-born residents. Let’s start with the straightforward correlations.

Traffic congestion grief

Few people like driving every day through start-and-start traffic. There is only so much enjoyment to be had driving downtown from Coquitlam or Surrey while listening, in captivity, to the radio. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives says the population of Metro has grown by more than 22 per cent since 2001, while the number of vehicles has jumped 37 per cent. I do not envy transportation planners and politicians their massive task, especially given the vocal anti-tax lobby.

Housing stress

When it comes to stress, the impact of the housing crises in Vancouver and Toronto glares. The Vancouver School of Economics study found Canadians are happier if they devote 30 per cent or less of their income to housing.

But the Royal Bank of Canada reports Metro Vancouver housing costs are an “astounding 85 per cent of a typical household’s income.” That compares to 78 per cent in Toronto, 22 per cent in average Canadian urban centres and six per cent in the hinterlands.

While windfall housing profits might boost the “happiness” of some real-estate industry officials and owners, the rest of us, including Helliwell, worry about the emotionally devastating squeeze housing is placing on Vancouver and Toronto dwellers.

High-density unhappiness

Even though neighbours aren’t physically close in small towns, they have more social networks than people in crowded urban centres, reports the study, based on 400,000 responses.

Meanwhile, even though the City of Vancouver proper is already the most dense region in Canada, and the core of Toronto is similar, lobbyists for the housing industry argue the answer to the affordability crises is to build even greater density. One wonders how that might make us more content.

Yet, as Helliwell says, “the moral is not that everybody should move to the countryside.” He talks instead, hopefully, about creating more green space and trying innovative “positive psychology” ideas that, for instance, get police actively engaging with young and old — before trouble strikes. “It can get people out of their silos.”’

Pros and cons of foreign-born enclaves

Pros and cons of foreign-born enclavesThe Canadian study shines light on one of the most sensitive and unexplored subjects in North America: the vagaries of rapid in-migration and super-ethnic diversity.

Some of the highest concentrations of foreign-born people in the world are in Metro Vancouver (at 45 per cent) and Toronto (49 per cent), while the country’s urban average is 22 per cent compared to six per cent in rural areas. The percentage of foreign-born is most intense in South Asian areas in north Surrey, for instance, and in ethnic Chinese sections of Richmond.

However, Canadian neighbourhoods with high concentrations of foreign-born residents do not emerge as more unhappy because the immigrants are unhappy compared to local-born residents. The World Happiness Report concluded migrants to relatively happy countries like Canada slowly end up with almost as much life satisfaction as the native born.

It’s not shocking that neighbourhoods with many foreign-born newcomers score lower for happiness, since other studies show people who live longer in neighbourhoods, and in Canada, feel a stronger sense of connection. Most foreign-born people “come from somewhere else and haven’t yet set down their roots,” says Helliwell, noting many initially choose transient neighbourhoods.

The authors wonder about the “puzzle” of why “migrants generally, and immigrants especially, choose to move to cities, and generally the largest and least happy of cities? Are they aware that life will be less happy there than elsewhere, do they hope and expect to beat the averages, or are they driven by other motivations?”

How does Helliwell assess the discovery by famed Harvard sociologist Robert Putnam that people in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods tend to have lower social trust? Although British research generally confirms it, Helliwell says “those who have been testing the Putnam hypothesis in Canada found it only marginally supported.”

Yet there is little doubt that barriers can be created by the rise of enclaves. “It’s easier to reach out to people with whom you feel at ease, and you feel more at ease with people with whom you share common ties,” says Helliwell. “People cooperate more easily with people with the same social identity. That also has to do with values.”

Related

- Douglas Todd: Canadians are more happy than ‘xenophobic’

- Douglas Todd: Bankers know why Metro housing costs ‘the worst ever recorded in Canada’

- Douglas Todd: Vancouver’s ethnic Chinese irked by housing inequality, tax avoidance

On occasion, Helliwell compares Vancouver to the luxurious French Riviera, where enclaves shaped by the status of the elite and ethnicity of the labour market have existed for a century.

“There are respects in which Vancouver is seen as a beautiful place to visit and even have a second residence. As is true of the Riviera …. Vancouver is too beautiful not to share, but it needs to be done in ways that build rather than fray the social fabric that supports the happiness of locals, newcomers and visitors,” Helliwell says. The pace of immigration, he notes, “makes a difference.”

Is there hope for Metro Vancouver and Toronto? When Helliwell talks to immigrant-settlement groups, he emphasizes the value of organizing silo-crossing events like neighbourhood block parties. And, all things being equal, he remains a fan of ethnic diversity.

“The building of social connections is complicated. It doesn’t work as well in cities as it does in areas that are less crowded. But where it works, it’s more fun to have a community that’s diverse. Diversity is an asset — if you have some kind of overriding social identity that makes you part of a bigger us.”

dtodd@postmedia.com

No comments:

Post a Comment